"For this Black History Month I want to flip the narrative and uplift the economic history of Blacks and their impact on our national economy."

Fay Horwitt

It’s February. Every year since stepping into a leadership role at Forward Cities, when this month rolls around, I have felt pulled to share a written reflection in honor of Black History Month, accenting the impact of Black entrepreneurship and business on American history. Writing is one of my passions, and typically I enjoy slowing down to write about this topic that is so central to my personal and professional identities. I assumed this year would have been no different. In fact, I assumed it would be the easiest yet. Forward Cities is currently deeply engaged in a program that’s catalyzing a cohort of North Carolina communities in exploring the past, present, and future of Black Wall Street. That blog would have pretty much written itself.

Fay and the Forward Cities team recently traveled to Lawrence/Douglas County, Kansas for the inaugural stop on the E3 Nation Tour.

But for some reason, every time I would sit down to write I would experience a major block. I can’t escape the feeling that there is something else I am meant to share. Looking for inspiration, I decided to do a little research. I have been celebrating Black History Month since I was a child but I realized that I didn’t know or, at least I couldn’t remember, the origin of the holiday. As it turns out, Black History Month, as we know it, came into national prominence only a couple of years before I was born. Black educators and Black United Students at Kent State University first proposed an official Black History Month in February of 1969; the first celebration of the holiday took place at Kent State a year later in 1970. Six years later, Black History Month was being celebrated across the country in educational institutions, centers of Black culture, and community centers when President Gerald Ford recognized it in 1976 during the celebration of the United States Bicentennial. He urged Americans to "seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history."

Essentially, the holiday has become a time when our country focuses on what prominent Black individuals have done that the broader society deems ‘exceptional’. However, when one digs deeper into the actual origins of the holiday, a very different narrative and intention is uncovered. Its precursor, Negro History Week, made its first appearance in 1926, championed by its founder, Carter Godwin Woodson, an American historian, author, and journalist considered the "father of black history." Woodson was an important figure to the movement of Afrocentrism, placing people of African descent at the center of society, the study of history, and the human experience. Hence, the original purpose was not to call attention to Black individuals that white society deemed ‘exceptional’, but rather to center the history and culture of all Black people.

Fay is pictured above with Martin "Marty" Watson, owner of Watson's Barber Shop in Lawrence, KS.

Reflecting on this, one strong observation immediately surfaced for me. The original intent was to center the Black narrative and lived experience which, in this country, is rooted in the strength and resilience of a people whose intelligence, ingenuity, and strength served to create the foundational wealth of this nation through their enslavement and forced labor. Upon gaining our freedom, our ancestors were able to forge their own burgeoning and vibrant local economies spurred by business and social innovations that birthed full, vibrant communities from the ground up in the span of just a couple of generations. This all happened outside of the broader white society at the time – and in spite of both unsanctioned and sanctioned attempts to arrest its development through violence, segregation, and policy. Yet, this is not the history that America wants to remember.

The current narrative around the celebration of Black History Month is a desire for our country to correct for the fact that the accomplishments of Black people have been intentionally and systemically excluded from our country’s written history; this includes Black entrepreneurial trailblazers. The reality is that it is more palatable for our nation to focus on the happy narratives of what Blacks in America have invented and done to improve society for all Americans than for us to face the realities of the contributions of the entire Black race to this country, particularly prior to emancipation. It was these contributions that in essence, served as the foundation for America’s rise to prominence and allowed it to become the economic giant it is. This narrative mostly swept neatly under a rug, is the key to understanding the American racial wealth gap. Unless we are all willing to collectively look at it, as ugly as it may be, and to invest in addressing the root causes, we will never be able to close that persistent gap. In fact, that risk is increasing as recent legislation seeks to curtail the telling of our authentic - and true - stories in the classroom.

So for this Black History Month I want to flip the narrative and uplift the economic history of Blacks and their impact on our national economy. If you are reading this blog, chances are good that you are already somewhat familiar with the abysmal state of the racial wealth gap in America. Using data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis found that in 2019 the median white family had $188,200 in wealth compared to just $23,000 and $24,100 for the median Hispanic and Black families, respectively. According to the survey, after a slight incline headed into the 2000’s, Black median household wealth is, once again, on the decline, while white wealth continues to increase. This means that the gap is not decreasing. In fact, it is increasing. In order to understand why we need to look at the history and foundation of entrepreneurial wealth in the United States.

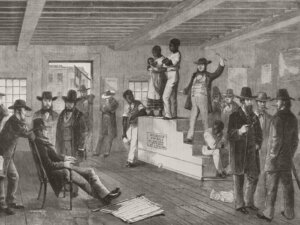

Photo: Rischgitz/Getty Images

The racial wealth gap begins with slavery itself, which was a huge wealth generator for white Americans. In his 1988 book, “Battle Cry of Freedom,” Historian James McPherson writes, “the economic value of the 4 million slaves in 1860 was, on average, $1,000 per person, or about $4 billion total. That was more than all the banks, railroads, and factories in the U.S. were worth at the time. In today’s dollars, that would come out to as much as $42 trillion, accounting for inflation and compounding interest. The bodies of the enslaved served as America’s largest financial asset, and they were forced to maintain America’s most exported commodity.” A little-known fact: slave-backed securities were one of our nation's first wealth-building vehicles. The profits from cotton propelled the U.S. into a position as one of the leading economies in the world. This is what should be deemed and acknowledged as exceptional.

This is the history that laid the foundation for the persistent racial wealth gap for Black Americans. This is the history that has caused deep, multilayered, generational trauma for Black Americans. This is the history that created the wealth of American corporate, financial, government, and philanthropic institutions as well as the venture capital landscape and wealth-building structures that continue to undervalue Black founders. This is the history that has impacted all Americans in some way whether by disadvantageing some or advantaging others.

"We all have an opportunity – in this very moment – to craft, articulate, and spread a new narrative that seeds a more equitable future. This is the history that we must look at, accept, grapple with, and collectively find solutions for."

I call these things to the forefront of our minds not to elicit feelings of shame or guilt, and certainly not of hopelessness. In fact, just the opposite. There is great hope. We all have an opportunity – in this very moment – to craft, articulate, and spread a new narrative that seeds a more equitable future. This is the history that we must look at, accept, grapple with, and collectively find solutions for. We should understand that we are living in tomorrow’s history today and we must take actions that our future descendants will look back upon and be proud of. I will call upon us all to consider our potential history in the making.

Imagine that it is the year 2123. A century from now, when our descendants are taught in school about this period of history. Let them read about this era with a definitive identity: the “Black Economic Renaissance.” Let them learn about how, as a nation, we:

- Dismantled America’s exclusionary economic systems that disadvantage Black Americans;

- Struck down government policies and bureaucracy that reinforce racist structures;

- Put an end to discriminatory lending practices;

- Exponentially grew Black ownership of commercial properties;

- Embedded entrepreneurial education into predominantly Black primary and secondary educational systems;

- Found innovative ways to integrate economic reparations into our business economy;

- Created new wealth building vehicles that align with Black culture and values;

- Exponentially increased the pool of Black business investors and funds;

- Passed new legislation that guarantees equal wages for Black employees; and

- Reinvested our growing wealth back into our Black businesses and communities to ensure perpetual sustainability.

Let that generation see that we were able to change history and to write a new narrative. Most importantly, let them look back upon us and see that together, through innovation, ingenuity, and connected networks, we were able to reimagine Black Wall Street and to close the racial wealth gap for Black Americans by doing whatever it took to transform the way communities – and our nation – see, support, and sustain entrepreneurs.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Fay Horwitt

President & CEO, Forward Cities

Fay serves as the President & CEO of Forward Cities, where she oversees organizational strategy. In addition, Fay is a dedicated advocate for the emerging profession of ecosystem building, and as a founding member of Ecosystems Unite. Beyond her formal roles, she is a sought after presenter, trainer, and thought leader on the topic of equitable entrepreneurial ecosystem building. Never one to be content with status quo, Fay has also recently begun addressing a new need in local communities: ecosystem healing–helping pivot ecosystems and institutions in this time of the dual COVID-19 and systemic racial injustice pandemics.