When Nicole Vigilante lost her part-time job as a dietician, she decided it was time to pursue something different. Vigilante, who was born and raised in New Kensington, Pennsylvania, started Trovo Co., a vintage shop. At first, it operated online, on Etsy. But, Vigilante said, “brick and mortar was always in the back of my mind.”

It was an audacious ambition. Brick and mortar had been crumbling in New Kensington for decades as the city suffered a long, slow decline. As industry departed, the once-thriving downtown—full of department stores, shops, and movie theaters—hollowed out, leaving vacant storefronts everywhere. The customer base shrank as the city’s population declined by half. Most new businesses that opened failed within a year.

It was not, in short, the type of downtown where you might think to set up shop.

Beyond questions of supply and demand, there was the matter of business knowhow. Community members expressed that a lack of basic business skills was inhibiting the success of local entrepreneurs. Vigilante was no exception: She didn’t have any experience or training in how to run a business.

But then she heard about a pilot program designed to train small-business entrepreneurs in starting and running successful enterprises. It was part of a broader initiative by Forward Cities, a nonprofit organization that supports communities to develop intentional strategies around building a community for and around all of its entrepreneurs, which encompassed small-business instruction, soft-skills training for job-seekers, and a communication hub that would connect residents to opportunities and support services. With financial support from the Richard King Mellon Foundation and partnerships with an array of local institutions, Forward Cities was aiming to help New Kensington get back on the path to growth, economic success, and employment.

It was no simple undertaking, in a city long beset by economic and demographic headwinds and, according to some residents, reputational problems and a resigned mindset that made it hard to effect change. But Forward Cities offered resources that had been lacking, experience in community-driven change, and collaborations with local stakeholders that could foster productive dialogue among segments of the population that had struggled to come together. Forward Cities received funding to work in New Kensington to convene a cross-sector coalition of local stakeholders to identify and implement pilot projects which would test how to best increase support and visibility for local entrepreneurs as well as expand opportunities for residents struggling in the local labor market.

About a year after Forward Cities launched its pilot programs in New Kensington, the outcomes of these efforts are becoming apparent. The project has been a clear success for both individuals and the broader community. At the same time, the initiative faced hurdles that offer lessons for similar efforts in the future.

The rise and fall of Aluminum City

No city’s trajectory can be pinned on a single factor, but New Kensington’s rise and fall tracks almost perfectly with the fortunes of the aluminum giant Alcoa. The company’s first incarnation, the Pittsburgh Reduction Company, set up shop on the banks of the Allegheny River in 1891, in the brand-new city of New Kensington, founded the same year. New Kensington first appeared on the census in 1900, with a population of 4,665. For the next 40 years, the number of inhabitants of Aluminum City, as it became known, jumped by around 50 percent every decade, and the downtown grew with it.

Alcoa-New Kensington Works, Steam Plant, New Kensington, Westmoreland County, PA

“At its peak, Alcoa employed almost 10,000 employees,” said Mayor Tom Guzzo. “So there was a necessity for a major downtown. We had five movie theaters downtown. We had not only five department stores, but also individual clothing shops and dress shops, and restaurants and things of that nature.”

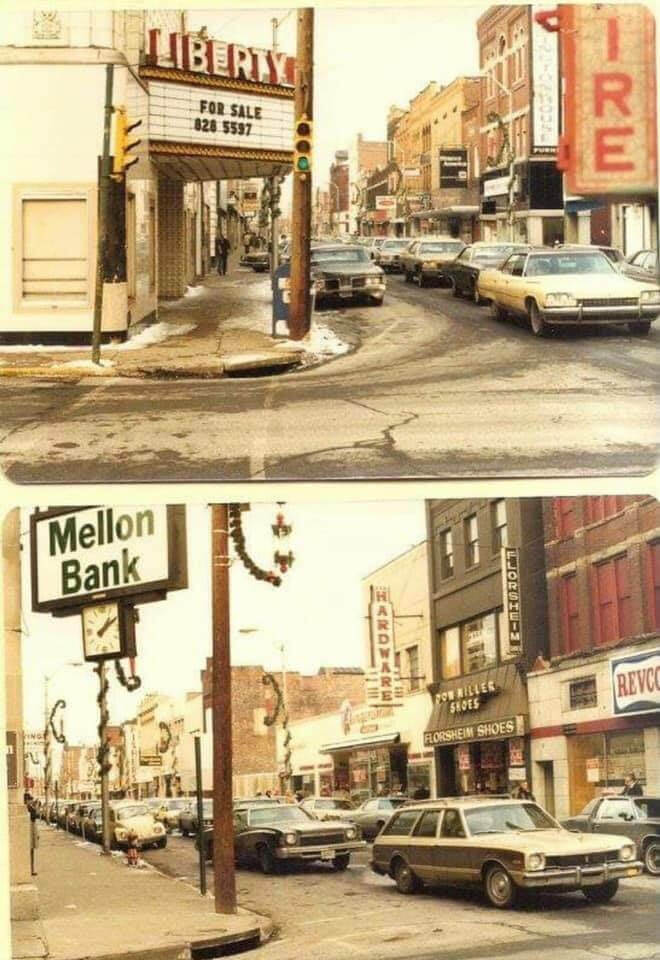

Then, in 1971, Alcoa left New Kensington. What followed was an exaggerated version of the Rust Belt decline that beset a swath of the country. Half the population disappeared over the subsequent decades, along with the movie theaters and department stores and shops. Vacancy plagued both the business and residential districts of town, with spillover effects.

New Kensington in 1978

“When Alcoa left due to cheaper labor going down south, when it lost its large presence here, at that time we had about 25,000 people, and we had about 7,000 homes,” said Guzzo. “Now we have about 14,000 people, and there are still some 6,500 homes.” Homes lost value, Guzzo added, and then “landlords come in and start renting them out cheap, so you’re attracting a different clientele. We battled that for quite a few years.”

With rising poverty—the city’s median household income is less than half the national average—came crime, or at least a newly visible kind of crime. In the city’s heyday, the Mannarino Mafia family controlled gambling rackets and much of city life. Following a government crackdown in the 1960s, the mob lost its hold on the city, and organized crime was replaced by street crime. In a diminished city, residents came to glorify the Mafia days and see the twin departures of Alcoa and the mob as the sources of New Kensington’s downfall.

All of this left the city with an array of obstacles to positive change. New Kensington has a reputation for crime, underinvestment, and a reticence to change based on a nostalgia for the so-called glory days. Employment downtown has shrunk, and inadequate public transit makes it hard for many residents to access the jobs that do exist farther away. Meanwhile, many barriers exist for both job seekers and would-be entrepreneurs which stand in the way of long-term gainful employment.

It is this environment that confronted Forward Cities as it came to New Kensington—and it is this environment that Forward Cities sought to help change.

Waking up the hidden hope

Forward Cities’ journey to promise

Efforts to turn around New Kensington were hardly new. People had gathered many times to develop plans that never came to be. There were individuals trying disjointed initiatives to alleviate poverty and improve employment opportunities that sparked initial excitement but then fell to disappointment when nothing came of them. Forward Cities’ announcement of its grant-funded work in New Kensington was met with well-honed skepticism among locals. “We had little hope, and it wasn’t going to help,” said Kim Louis, a local nonprofit director, of the prevailing sentiment. “We’ve had these conversations 100 times, and everyone wants everyone else to do the work. Let’s go ahead and try this, but I don’t think it’s going to go anywhere, because nothing else has. I think that was the attitude of many going in.”

"Whenever I came to New Kensington it became clear to me there was nowhere for the town to go but up."

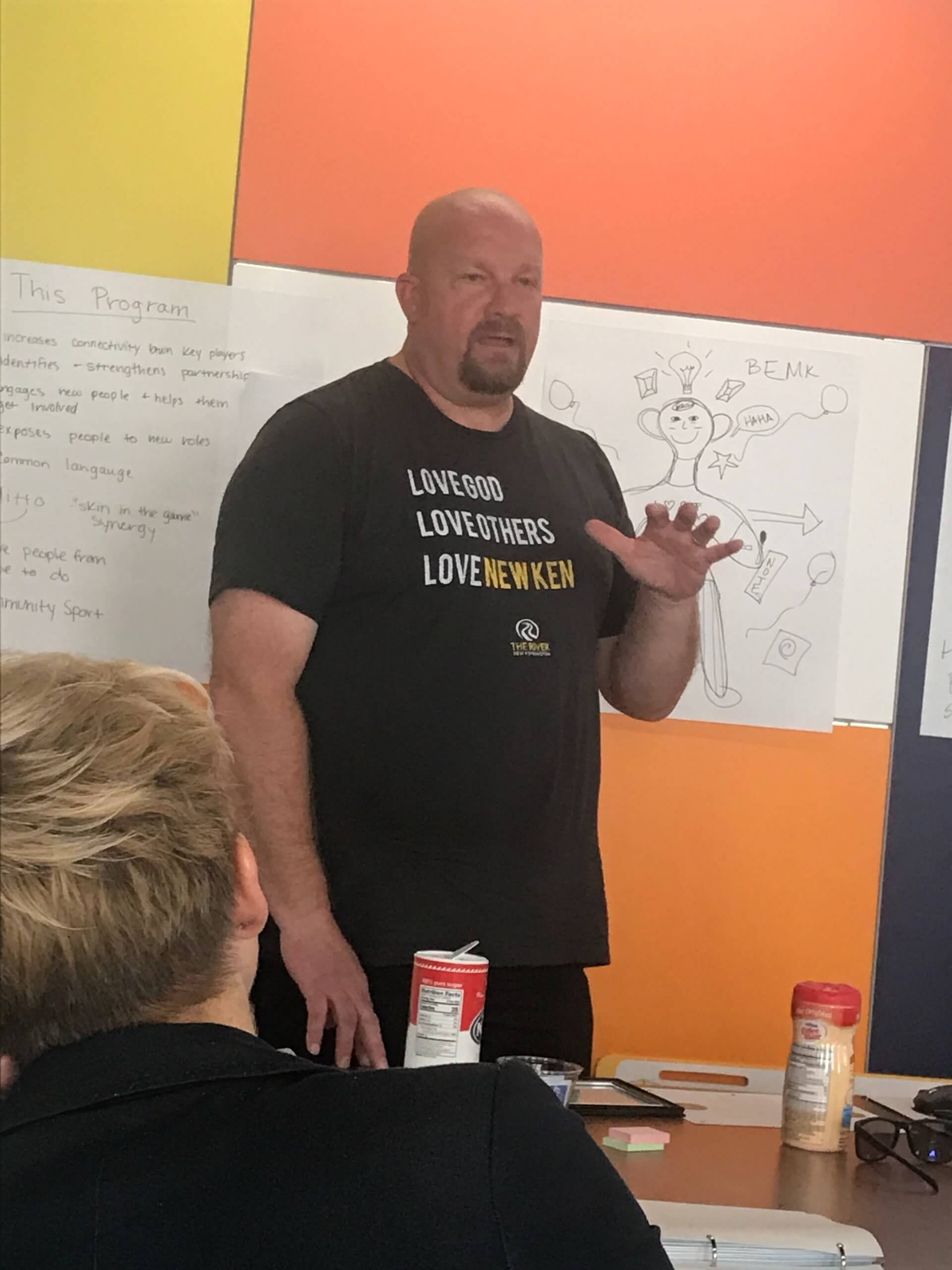

Dean Ward, Pastor of The River Community Church who was involved in some of the Forward Cities council process states, “when I moved to New Kensington in 2002 and my wife and I decided this is where we wanted to raise our family, I knew that downtown New Kensington was just about at its lowest point. I heard stories about the glory days and I did not experience those days, personally. Whenever I came to New Kensington it became clear to me there was nowhere for the town to go but up. I wasn’t grieving the loss of all that had been. I saw the hope and potential of all it could become. It was interesting to me that the people who grew up here did not share that optimism.”

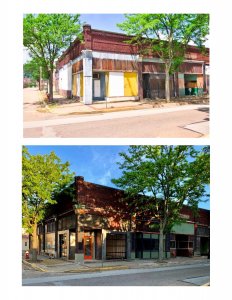

Many initiatives began to emerge at the same time as people began to reimagine what downtown New Kensington could become. “The first time I walked down the streets of New Kensington, I saw the possibilities, but it was shells of buildings,” said Rhonda Schuldt from Penn State, who’s been involved in the city since the summer of 2018. “There were maybe three or four businesses at the time” on the stretch of Fifth Avenue that’s now called the Corridor of Innovation.

Better Block Events began in 2015. As Ward describes, “It was a momentum building pop up event to get people to come into downtown New Kensington and remember what it could be… because any time you’re in a 100+ year old community you are both looking back and forward… It’s impossible to be in downtown New Kensington and not be touched by what it used to be… [Better Block] reminded people of what it could be… It got people coming into New Kensington for an experience that touched all of the senses and engaged people in a different new way.”

Ward also recalls the first tangible investment in the new New Kensington, the opening of Knead Community Cafe in January of 2017. Knead, as the organization describes itself is a “unique gathering place that nourishes both body and soul. Offering meals that are pay-what-you-can / pay-it-forward, through fresh, wholesome food that is seasoned with love, where all are welcome.” He said, “The hope of it started to wake up this sleeping potential that there is a lot of room in New Kensington for good things to come. Nobody was willing to dive into the deep end first until Knead put a stake in the ground to make it happen. Knead is the single most visible entity that invited the entire region back into downtown New Kensington for the first time in decades. It was no longer talk, it was real and happening.”

As Knead was opening, a Penn State initiative was underway. A vision for an entrepreneurial coworking space through many partners including the City and Westmoreland County led to the opening of The Corner later in 2017. Penn State began to pay greater attention to 5th Ave as The Corner was posturing to open and they collaborated with The Community Foundation of Westmoreland County to launch the space with an Arts and Music Festival, bringing together the community. This built on the foundation of the Better Block Event and further developed initiatives in downtown, helping it to become a place people would want to invest in. The event included facade grants and the development of a parklet, improving the look of the street and drawing attention to the few glimmers of hope that were already there.

Development of 5th Avenue, photo by Mike Malcanas

In 2018, the regional Chamber of Commerce brought their Wine and Beer Festival to 5th Ave, bringing even more attention to the Corridor of Innovation. And more things than festivals all started happening at the same time—investors were buying buildings and fixing them up, Penn State began talking about high level training to help bridge the digital divide and prepare the workforce for the future through their Nextovation initiative, and the people involved in all the projects recognized the need to make all these things accessible to the people who live in the local community. Nextovation is a collaborative effort by Penn State New Kensington and the Richard K. Mellon Foundation to build a digital innovation lab in the heart of downtown that would serve as a training facility and 21st century manufacturing lab for local residents to utilize. This effort was seen as being catalytic for the community, but there was a perceived need to develop programming that could serve as a bridge to the lab’s opening. That’s what opened the door for Forward Cities involvement.

Phil Koch, who worked as the Executive Director of The Community Foundation of Westmoreland County explained, “There were a couple things at play—a lot of different people working in a lot of different ways with a lack of coordination and getting on the same page. There was an anticipation of significant investment [into Nextovation] and the worry it would turn into gentrification instead of a community-based process and support the folks who were already there. I had no evidence it was going to work, the principles that Forward Cities stood on were in line with my perspective into creating an equitable ecosystem in New Kensington.”

The process Forward Cities recommended was called a Readiness Assessment, which would help the engaged community stakeholders collectively discover key areas of focus and design strategies to overcome barriers to success around workforce development advancement and small business support.

Struggling communities are well acquainted with the phenomenon of well-meaning outsiders coming in and thinking they can fix the problems locals have been tackling for years. New Kensington was no exception. “It was a little rocky in the beginning, quite frankly,” said Kevin Snider, the chancellor of Penn State New Kensington. “We had already been involved in this space.”

While skepticism existed in the early stages, it was largely put to rest when Forward Cities actually got to work. Rather than follow a prescribed program model, Forward Cities invested significant time and energy consulting with the local community on its needs and desires. Perhaps the team’s biggest early success was convening an ‘Innovation Council’ consisting of a diverse array of community stakeholders, from unemployed and homeless residents to university leaders. The council used an ecosystem canvas, a facilitation tool developed by Forward Cities, paired with a compression planning process to come up with a short list of agreed-upon target outcomes and the first steps toward achieving them. “That’s how we built the trust, by coming to a consensus on what we agree on,” said Louis. “We want businesses downtown. We want empty lots used. We want the crime to go away. We want it cleaned up. We want the people who live here to be able to work here too.”

New Kensington began the process of creating the local Innovation Council in October of 2018. Initial meetings were held with Forward Cities national staff and community stakeholders to design the engagement. In November of 2018, the council broke into two sub-committees to begin working through the barriers to equitable workforce and entrepreneur participation in the community, while Forward Cities began searching for a local project manager. It was important to the council that the project manager came from the community. A job description was sent out for collecting resumes. Jerry Jefferson, local entrepreneur and community leader, recalls designing the Forward Cities engagement, “at first I thought Forward Cities were some outsiders coming into our community to fit us into their template vision. After participating in the meetings and the process, I was pleasantly surprised to see their desire to help our community discover and develop our own vision.”

Kim Louis was not at the initial design meetings. She was invited into the process separately by both Jerry Jefferson and Phil Koch, both of whom participated in the early conversations. Her community involvement as a local non-profit director helped her gain trust from community members and community leaders alike. Louis is a homeowner in downtown New Kensington and has served the community since a year before she moved there. When she heard about the opportunity, she could not help but apply because, as she recalls, "when I read the job description, I couldn't help but think it was describing me." In December of 2018, Forward Cities extended an offer to Louis to become the local Project Manager.

Efforts were made to get input from a larger cross-section of the community beyond the people who originally designed the Forward Cities engagement. In addition to representatives from Penn State New Kensington, council members were added who lived in neighborhoods that had been impacted by the community’s historical barriers: a woman rooted in the community who was homeless at the time, a local African-American barber who had done business in New Kensington for over 25 years, a single mom who was unemployed, a local African-American pastor and his wife who supported people in poverty, and entrepreneurs who couldn’t quite get their businesses off the ground. Other participants included the leaders of Knead Community Cafe (who worked in grassroots workforce development), Careerlink, The Corner, The Redevelopment Authority, Kingdom Men in Action, Wesley Family Services, The River Community Church, New Kensington and Arnold School District, Alle-Kiski Chamber of Commerce, Westmoreland County, and the New Kensington Mayor’s office.

At the beginning of 2019, the Council began working through the canvas. There were so many ideas about what the priorities should be that the Forward Cities team facilitated a compression planning process to honor them all. A voting process was used to gain consensus on what the council would prioritize in the strategic planning process. Committee and council meetings continued every few weeks between February and April of 2019. The final meeting was held on April 30, 2019, at which point the canvas process was complete.

On May 21, 2019, a local convening was attended by 43 people who affirmed the recommendations of the local council. Nine members of the Innovation Council attended the Forward Cities National Conference in Pittsburgh held from June 12-14, 2019. The Readiness Assessment engagement officially ended July 3, 2019. Follow on funding was secured to invest in a set of pilot initiatives that were launched in the summer of 2019. These pilot initiatives were evaluated throughout the implementation period and a set of recommendations to sustain the momentum and deepen impact was presented to stakeholders and funders in March 2020 for next step consideration.

“At first I thought Forward Cities were some outsiders coming into our community to fit us into their template vision. After participating in the meetings and the process, I was pleasantly surprised to see their desire to help our community discover and develop our own vision.”

Getting the work done

a community rolls up its sleeves

Restorative Justice Mural, Photo by Kim Loius

Doing work in any community is messy and a diverse council brought diverse opinions and ideas of what was most important to support. The Innovation Council had 45 people on the contact list. Early on in the process a compression planning system was implemented to help gain consensus on what ideas should be developed. The process allowed the group ideas to rise to the surface over any one individual voice. The strength of this approach was the ability to honor all ideas, but narrow planning to things in which the community would invest.

No one loves meetings, but Forward Cities’ commitment to showing up and holding regular community meetings had an impact. “They continued to have meetings,” said O’Domes. “If people didn’t understand, they changed tactics in how they explained it. Kim was always there directing, and that helped. We stayed involved because we stayed in communication with each other.” It helped that Forward Cities was coordinating among the different players involved and could answer the community’s questions. “When you’re at a meeting, and you’re talking about all these things, and you go, ‘Well how are we gonna pay for this?’ and the money guy is sitting over there and going, ‘This foundation, that foundation, that’s how we’re gonna pay for it,’ it puts a lot of minds to rest,” he said. “They had everybody at the table who needed to be there from the beginning, and they stayed involved.”

The process achieved an important measure of community buy-in. The council reached a consensus on what longer term target outcomes for the community would be. These outcomes were developed with a long-term mindset, and served as the basis of understanding for the development of more immediate goals, which largely informed the solution creation process.

The identified target outcomes were:

- Decrease the number of unemployed community members by 20% in three years.

- Double the number of people from vulnerable populations (identified as zip code 15068) engaged in workforce development programs within three years from 1,415 people to 2,830 people.

- Increase in number of occupied storefronts in downtown (identified as the Corridor of Innovation) by 60% within three years, from the current 40 to 64.

- Increase the number of locally owned businesses in New Kensington (identified as the Corridor of Innovation) by 20% in three years.

From these target outcomes, the council used the compression planning process to brainstorm what first steps could be taken to achieve them.

Three pilot programs (or Minimum Viable Solutions, as Forward Cities calls them) would be tried out over the coming months to discover what worked and efforts would be made to find local support to continue them within New Kensington’s ecosystem: business development through entrepreneurship instruction, a workforce development initiative focused on soft-skills training, and access to information and resources through a communication hub.

In the case of two of the pilots, local options were uncovered and applied, but when it came to the entrepreneurial education pilot, Forward Cities determined the work of Co.Starters, a small business coaching organization out of Chattanooga, TN, would be the most ideal fit. Unsurprisingly, it would prove to be a challenge to adopt locally.

Building business sustainability

Louis believes the Co.Starters curriculum to train entrepreneurs in business skills was the most successful of the three Forward Cities initiatives. The program serves as their foundational offering—a cohort-based program designed for 10–12 weeks that equips entrepreneurs of all kinds with the insights, relationships, and tools needed to turn ideas into action. Fourteen entrepreneurs participated in the first Co.Starters cohort. Eleven of them already had businesses in operation, and nearly a year later, all 11 of those businesses are still open—a remarkable track record as COVID has decimated small businesses around the country, and all the more so in a city where new businesses frequently shut down. Of the three new startups, one is in the process of obtaining a space, according to Alyssa Pistininzi, who manages The Corner, the coworking space and business support center that hosted the Co.Starters program. The other two have opened their storefronts.

The Corner Launchbox, photo by Penn State University

Before Forward Cities arrived, The Corner already hosted Penn State New Kensington’s “Launchbox,” an entrepreneurial startup center that’s part of most Penn State campuses. So there was initial skepticism when Forward Cities introduced the Co.Starters curriculum as a proven model to expand entrepreneurship education through a train-the-trainer model. “They brought Co.Starters to us,” said Rhonda Schuldt, the innovation coordinator at The Corner Launchbox, “and it was like, ‘What is that? Cause we do programming already.’ There was this sense that they were bringing something to us that we weren’t a part of creating. So there was trepidation. There were partners we work with who said, ‘We all do programming. Why is this being brought to us without us having any say?’”

Co.Starters began with a facilitator training in October of 2019 that walked 9 stakeholders through the process of delivering the curriculum. “That training turned minds around,” Snider said. “It was unbelievable. Forward Cities knocked the ball out of the park with that thing.”

The curriculum quickly won them over by addressing the needs of basic main-street businesses. “We were pleasantly surprised that it provides a structure and a language for us to work with people at a community level, in businesses from main street to manufacturing,” Schuldt said. “Because if you’re trying to start a bakery and you’re talking at a biotech level, nobody wins.”

This typifies the approach Forward Cities takes, seeking out the best resources for the stated need, even if those resources come from national service providers. The understanding they have built in years of doing this work helps to inform the decision-making process in ways local coalitions often cannot do on their own. "Forward Cities' past experience working in mid-sized cities that experienced rapid de-industrialization like Cleveland, Detroit or neighboring Pittsburgh, was seen as a real asset that we bring to the table. We don't presume that we have all the answers, but we have a special perspective on models and programs from across the country that assist communities in revitalizing their economies,” said Fay Horwitt, who had great influence on the development of these relationships and a major role in program development.

That said, the language disconnect has been an issue at times. Snider was a driving force behind the whole initiative—long before Forward Cities, he had taken the lead on revitalizing New Kensington through business development—but he’s a big-picture guy, more likely to talk about the broad sweep of technological change than how to get funding to put up a new awning. Asked whether a high-level tech approach is really what’s needed for someone trying to start, say, a hair salon, he responded, “My feeling is that the person who wants to start a hair salon, it’s great to get them started in that model, but we have to get them thinking about what’s next. What’s the next technology in hair coloring, or growing hair on bald people?”

Forward Cities helped bring the discussion back down to the community level. Many businesses do need to prepare for the technological future—Snider rightly pointed out that the businesses that survived in COVID were largely the ones that succeeded in using the internet to make sales—but the challenges facing New Kensington businesses were more fundamental. “A lot of it was, they don’t understand that threshold between starting the business and when you make money,” Louis said. “They put all their gusto into a storefront, and then they fail because they can’t pay their employees.” The main need was to teach basic business practices.

For some participants, that initially felt too elementary. “They came into it thinking, ‘We’re already established businesses, we already know most of this stuff,’” said Pistininzi. “But it really helped them reexamine the way they were doing things, and think about things differently. And by and large the feedback was very positive.” Peer-to-peer support and dialogue among the participants was often as valuable as the curriculum itself.

Co.Starters Training in progress

Autumn Walker, local Corridor of Innovation shop owner, wrote about her Co.Starters experience: “I have learned so much from the program, both when I took the facilitators course and as a participant. My biggest takeaway that isn't from the teachings is the much stronger sense of community the program has instilled in us by having open conversations and working together which is so amazing. From the trainings though, I really learned so much from one of the guest speakers we had, Matt, who spoke to us a good amount on crowdfunding. Many of the things I had learned about are no longer true or relevant. It made me realize that while I might know a good deal on a topic, that things do change and to never forget to take the time to reexamine to make sure the facts that I have are still relevant.”

AJ Rassau was one of the participants who already had a business track record but benefited from both the lessons and the network. He’d started a record store and concert venue called Preserving Underground and was in the process of expanding his business. “I’m still at zero employees,” he said. “I run the whole thing myself. For me to dedicate my time to something, there has to be an incentive.” As with other participants who completed the program, AJ received a $1,000 microgrant that he used to expand his PA system.

At the same time, he found the lessons valuable, and he said he wouldn’t have signed up for the coursework or the grant alone; the combination was what made the program appealing, along with the networking potential in a town where personal connections are important. He thinks he probably would have had the same business success without the program—he calls himself a “jump-in-the-deep-end personality”—but he observed classmates learning key information for the first time.

Rassau was lucky to be in the sweet spot among the participants: neither too green to follow and apply the lessons nor too experienced to find them useful. “There were some people that were 10, 15 years into doing their business, and there were some people who just had an idea,” he said. Ideally, he felt the program could have divided participants up by experience, but that would only work with a bigger cohort; in a class of 10 to 12 people, it’s not feasible.

Betsy Shelhammer owns a business with her husband and has been on 5th Ave. in New Kensington for over 20 years. “My biggest takeaway from the Co.Starters program is the verbal interaction we had with each other. Learning new techniques from others, what worked, what failed. The support I received and I saw given to myself and one another by people who were just strangers only weeks earlier. I got to learn who and what other small businesses are in my town. Being a small business, I hadn’t taken the time to delve into relationships with other small businesses in my town. I am grateful for your giving me this opportunity. Our moderators were fantastic! By sharing their experiences, we as a group opened up to each other within the first week. Amazing! Kudos to them!”

The existence of The Corner, anlong with the involvement of Snider and Penn State, paved the way for Forward Cities’ intervention. But the Co.Starters program also brought additional benefits to The Corner and the university. Beforehand, “we originally had a hard time getting people in,” said Snider. “Penn State is the whitest school I’ve ever worked at. And people would walk by [The Corner] and look in and say, ‘This is just for those rich white people.’ Forward Cities helped us break that down through Kim [Louis], because she’s got that standing in the community.” Now, he says, there has been an unprecedented growth of the people of color taking their entrepreneurial training. Snider also hopes the program will make Penn State more attractive to prospective students who want a digitally minded education and want to help revive a struggling Rust Belt town. “We’re gonna recruit the hell out of this thing,” he said, adding, “The fact that we are the poster child for community engagement in the Penn State community is bringing us additional resources.”

The Co.Starters program was initially designed for a single cohort, but due to its success and popularity, it was extended to a second cohort. It significantly exceeded its goal of a 75 percent completion rate; in the first cohort, all 14 participants finished the program, and in the second cohort, 14 of 16 did—an impressive number given that the instruction had to be moved online partway through due to COVID.

The most visible success of the general progress is the downtown streetscape. Much of this streetscape progress came from parallel efforts, but it speaks to the collective energy that had developed and was now starting to manifest. “The first time I walked down the streets of New Kensington, I saw the possibilities, but it’s shells of buildings,” said Schuldt, who’s been involved in the city since the summer of 2018. “There were maybe three or four businesses at the time” on the stretch of Fifth Avenue that’s now called the Corridor of Innovation. The revitalization began several years ago, but the improvement over the past year is undeniable and stands in contrast to most other downtowns in the country. “Our downtown, even with COVID, is better than a year ago,” said Louis.

That said, COVID-related shutdowns didn’t make things easy for the Co.Starters program. “We went from having a very successful Co.Starters program, where all our small businesses were excited and gung ho and ready to implement things, to closing within a week,” said Louis. But ironically, downtown New Kensington’s long standing struggles may have actually positioned it well to bounce back from COVID. “I don’t think COVID hit us as hard as other communities, probably because we weren’t open for business yet,” Louis said. “There was one business per block, maybe. And so post-COVID, New Kensington opens for business, and now other communities are paying attention because the things that we have are fresh and new.”

For all the success of Co.Starters, some members of the community still wished that Forward Cities had been more collaborative in designing and implementing the program. Any time there are multiple parties working collaboratively, there is not a straight path forward and there are challenges meeting the expectations of everyone in the group. This was demonstrated as the plans for Co.Starters were developed and implemented. Schuldt recalled, “It was given to us: This is what your solution’s going to be.”

That not only created tensions at the start, but it complicates the transition period after Forward Cities leaves. “OK, you’re doing your pilot, but then you’re gone,” she said. “What do we do next?” The Corner has traditionally offered its programming for free, whereas Co.Starters suggests charging participants. Forward Cities covered those fees for the first cohort of the program and had leftover funds for further assistance, but Schuldt worries that the cost of Co.Starters will be a barrier to participation in the future in New Kensington.

“What we do next, we’ve gotta figure out,” she said. “But we weren’t part of how to figure that out at the beginning. We haven’t been part of the conversations within Forward Cities or with Forward Cities and the funder to say: This is great, but if this is successful, how do we play it out moving forward and integrate it into the programming and those community partners that exist?”

To alleviate this challenge, Forward Cities used pilot funds to assure that there would be no cost to participants during the pilots and to secure sustainable resources from Co.Starters for LaunchBox so that they can deliver the program for posterity. Koch observed, “The whole reason we brought Forward Cities in is the benefit of the community process to listen, and understand current needs. The benefit is they are bringing in a national perspective, so they are able to suggest a successful program used somewhere else because the objectives align to the needs described by the community. Even though it seems like something new and different, let’s give it a shot. It can sometimes be uncomfortable for people and organizations. Many of the people are connected to organizations who should be doing this work and if they are not doing it, that can feel threatening, and I think that’s where some of the questioning was coming from.”

“Our downtown, even with COVID, is better than a year ago.”

"We don't presume that we have all the answers, but we have a special perspective on models and programs from across the country that assist communities in revitalizing their economies."

"Being a small business, I hadn’t taken the time to delve into relationships with other small businesses in my town."

“They don’t know, you have to teach them”

Jumpstarting career success

Council conversations surrounding barriers to employment were a common theme. Comments regarding eye contact, how people dress, use of slang, language in resumes kept coming up. There was an edge to the conversation where some council members were finding fault with the people who needed these skills. The conversation moved to support instead of judgment when Joan Scott, co-founder of World Overcomers Fellowship, said, “they don’t know, you have to teach them.” It was that statement that led to designing a soft skills cohort training for people in the community who lived in barriers that exist with poverty and justice involvement. It was like a lightbulb went on—if someone is lacking a skill, we can create something to bridge them to that skill.

Benjamin Murray-Sinicki was finishing his degree in computer technology at Westmoreland Community College when his wife told him about something she’d seen on Facebook: a new job training program focused on soft skills. “She said, ‘Hey, they’re having a program at the community college, you should try this out,’” he recalled. “‘And you get a $100 gift card.’ I figured, hey, 100 bucks if you do the training. It can literally only benefit me, so why not?” He signed up and brought his sister along, too.

The Jumpstart to Success program was the result of input from community members about a lack of basic skills needed to land a job—something Murray-Sinicki had observed. “People were absolutely lacking in the skills, mostly because there aren’t a lot of white-collar jobs in New Kensington,” he said. The problem was particularly acute for poorer residents, elderly people who had been out of work, and people with a history in the criminal justice system.

The idea of the program was to teach fundamental skills like how to dress for an interview and how to make eye contact, using a cohort model to allow participants to support one another. Forward Cities worked with the New Kensington office of CareerLink and the Pittsburgh-based Auberle Center to run the program. Auberle had ample experience training people in soft skills but had never worked in New Kensington, and the selection of a perceived outside organization to run the trainings irked some residents.

“Forward Cities was relying on Auberle, but there were people in the community who were doing similar things, so that created some animosity,” recalled Snider. He added, “Auberle was going to be in and out, and we’re sitting here with all these people in the community who were trying to get involved.” In the future, Snider said, “It might be useful for Forward Cities to go in and assess what are some of the local vendors and train them.” While that sentiment certainly deserves attention, the focus of Forward Cities falls short of actually upfitting existing organizations to deliver new programming. They saw Auberle as an organization ready to deliver on what the community had expressed was a pressing to be addressed. Additionally, the recommendation of Auberle actually surfaced during council meetings from a local stakeholder.

In terms of delivering on the training, Mayor Guzzo said Auberle dispelled any resentment. “There’s always a turf situation in life,” he said. “But the folks who came in were professional. They contacted me and wanted the lay of the land.” In fact, he said, sometimes it’s better to have outsiders bring a fresh perspective, since locals can have rigid preconceptions about how things should be done. “Our biggest asset is our people,” he said, “but they can also be a liability.”

Ultimately, Auberle delivered three Jumpstart to Success Cohorts, went on to find follow-on funding, and was able to set up a social worker in the community to see people in the council identified barriers through to job placement. Not only does Auberle support the soft skills, but through their social worker, participants are supported in workforce needs beyond the training. This provided a much needed support for the city.

Jake Markosky facilitating the Jumpstart to Success course

Auberle saw the engagement in New Kensington as an opportunity to expand into a new community according to Abby Wolensky, the deputy director of the Auberle Employment Institute. “This was our foot in the door to bringing our model, which is working from the inside of the business out to sustainable employment. It is no different than the other communities we serve and we wanted to bring our services there,” said Wolensky.

Some participants, like Murray-Sinicki, were motivated by the cash incentive, which was a subject of controversy on the Innovation Council. “There was a lot of conversation on our council about, why are we paying people?” Louis said. “There was talk of controlling what the money was spent on.” She went on to say, “how can people know their time is valuable and worth money if we don’t show them? How can people learn to be trustworthy if we don’t trust them?” Rodney Prytash of Auberle said the incentive was “very helpful” in motivating people to join, especially people who might have to miss some work to participate.

Tammy Croyle, a CareerLink program supervisor, said turnout for the trainings fell short of optimal expectations, in spite of the cash incentive and the meals that were provided. For some participants, the course might have been more intensive than they anticipated. “Maybe you could conduct some meetings, explain the programs and their intensity before people start,” she suggested. “Maybe that would get people to stick with it.”

Jake Markosky, a social worker from Auberle facilitated the Jumpstart to Success course. “We did have some individuals who would fall out or drop out for various reasons, but I believe some of those reasons were that they actually did obtain employment, and one of them had to move. The ones that were able to attend were very willing to work.” The program hit its attendance and completion goals across the three cohorts: having 75 percent of participants attend at least seven of the eight sessions and having 75 percent of starting participants graduate. The fact that the program extended to three cohorts, even after COVID forced it online, also speaks to its continued popularity and demand.

One challenge in running the program was tailoring the curriculum to the diverse needs of the participants, including older people who had been out of work for a while or had never conducted an online job search before. Murray-Sinicki found that the program seemed designed for people without any education beyond high school. He found it “extremely easy,” and while it was helpful to get a refresher on some things he already knew, he sees no reason not to make it more challenging. “It’s a risk to provide more engaging content, but at the end of the day, you’re not graded on your assignments,” he said. “If you show up and complete your assignments, you get the $100, which I think was the main incentive for people showing up.”

The benefits of the class went beyond the curriculum, though. To Louis, the most valuable part was coaching from the instructors, who set an example for the participants. The cohort model gave participants confidence they may have previously lacked in seeking employment. Still, it was hard to draw a direct line from the trainings to job-seeking successes for the participants.

For Murray-Sinicki, the process ended with a job. He’s now working at Pomeroy IT Solutions in Pittsburgh—“basically when something breaks, they call me to fix it,” he said. He can’t be sure to what extent the training helped him land the job. “I think I would have gotten the job without the class,” he said. “But I think the class significantly increased my chances since I was able to put this on my resume, and I was more prepared for the interview.” Regardless, now that he’s working, he feels better prepared for the kinds of employment challenges that aren’t taught in school: how to react to difficult workplace situations, how to convey personal challenges, and how to reach out to colleagues for help.

This opportunity opened up continued support in the future for New Kensington, as Auberle received follow on funding to scale up their programming. Wolensky explained, “What makes Auberle different is that we are not going to place someone in a job and say good luck, we are going to support them in that. We want to make sure people are successful from the first day of work. We want to make sure we are tailoring those placements to the needs of those individuals.”

"How can people learn to be trustworthy if we don’t trust them?"

"Get the word out there"

Communicating opportunity

Carnegie Mellon students watching a presentation.

One of the barriers to employment and stability identified by the New Kensington community is a lack of information. So the council that had convened to inform and design the pilots decided to build a central communication hub where residents could be connected to job opportunities, social services, business prospects, and other key information that was previously scattered among many hard-to-find sources. Of the three interventions, this is the hardest one to assess, since the hub—dubbed KenNext—wasn’t publicly rolled out until November 2nd and the pilot period has not yet concluded, but some themes emerged from the process of creating it.

Rick O’Domes, who had been an integral part of the local council, envisioned an interactive hub, where anyone in the 15068 ZIP code could search for whatever they needed and the site would connect them to the people who could provide it. There would also be a function to track the resident’s progress. So if, say, someone needed funding to buy a car, O’Domes would receive the request, connect the person to a source of funding, and then be able to track whether the loan came through.

That is not what happened. On launch, KenNext consisted of a series of links to existing resources with an accompanying way for users to send a message to the moderators of the site. Someone searching for a job would click a button for job-hunters and then be brought to a page with links to LinkedIn, Glassdoor, Monster, Indeed, and ZipRecruiter. Users can also search for entrepreneurial support organizations and social services to meet their felt needs while they are waiting for workforce supports to be put in place.

Forward Cities brought on a group of master’s students from Carnegie Mellon as interns to create the communication tool, and O’Domes felt there was a disconnect between the New Kensington team and the students. “When we all got our marching orders, I don’t know that they understood it like we understood it,” he said. “Kim was working very hard to get them on track. They really really tried, but I don’t think they understood where we wanted to go. Their vision, what they saw it being, was way different than what I saw.”

The reason was money. According to Louis, the Carnegie Mellon students proposed a $70,000 product that would take more than a year to build, whereas the New Kensington team had just $15,000 and five months.

“Their vision was to have it back-and-forth, interactive, but when we looked at the cost, we just didn’t have the money,” said Steve Leonard, a Carnegie Mellon professor who worked on the project. “So instead of waiting and not doing anything, we decided, let’s make [a basic system] that can at least get information out to the citizens and community members. It doesn’t necessarily need to be interactive.” The hope was that it would be a sufficient proof of concept and learning experience that the funds for an interactive site could be raised later. The current KenNext tool was designed by an outside web designing company, Wahila Creative.

Kim Louis, far right, with Carnegie Mellon students

“The work that was done by the students and by Kim is really good,” he said. “It basically left the door open and showed how you can go to the next level. And Forward Cities was really good in helping us financially try to get this thing developed.” Now he’s concerned with keeping the project going once Forward Cities own grant-funded engagement in New Kensington ends. “When you go through a process of handing this off, you don’t want to lose that momentum and energy,” he said. “We have to make sure we have folks who are willing to invest into this, because money doesn’t grow on trees.”

Compared to Jumpstart to Success and Co.Starters, which offered financial incentives, it can be more challenging to drum up interest in an internet portal that can sound amorphous. The soft launch of the tool in early October had over 1000 searches by over 100 people in the first week.

“We’re going to have to do more advertising,” O’Domes said. “There are a lot of group pages—not just Facebook and Nextdoor—we’re going to have to be on all those letting them know what we do. We just need to get the word out there.”

The tool is currently being managed by a student intern through The Corner. There is a BoyScout working on his Eagle project by adding a youth section to KenNext to provide a list of resources for students making educational recovery following COVID. Several community members are still collaborating to expand the tool and make it more relevant for the community.

The lessons from New Kensington

The general consensus among people involved in the Forward Cities New Kensington project—from the people who designed and led it to the participants in the programs—was that it was a success. Drawing lessons from the experience, however, is more complicated. For one thing, the project received generous local funding from the Richard King Mellon Foundation. Not every struggling small American city can hope to have a neighbor willing and able to contribute the catalytic funding necessary to deliver programs and alignment in this way.

New Kensington is also unusual among American cities in that its challenges transcended and often ran counter to common issues of race: In New Kensington, Black men actually out-earn white men in some areas, although Black women earn the least. In cities with more pronounced racial income gaps, the lessons of New Kensington might not be transferable. In addition, although Louis was concerned at the start of the project with avoiding the type of gentrification that had accompanied revitalization projects in parts of Pittsburgh, Guzzo insists that New Kensington is just not at the point in its economic development where high costs and displacement are a major risk. Other cities might have to be more deliberate about avoiding displacement as they undertake revitalization efforts.

But there are still instructive themes from the New Kensington experience for future interventions, whether through Forward Cities or other organizations. One is the importance of hiring the right local project manager. There is universal agreement that Louis helped bring different groups of people together and unite the community behind the project. In her 11 years working in New Kensington, Louis has formed deep connections with the community. She lives in a high-poverty neighborhood and feels personally affected by the city’s problems. Asked what made her a successful project manager, she said, “I don’t mind not being in the spotlight. I’m really good at connecting people and helping people have the conversations that they need to have without it turning into conflict and hurt feelings.”

At the start of the process, Schuldt said, there was great community engagement. “But at the end there was hardly anybody in the room,” she said. That worried her, because the project would only be successful if New Kensington was able to sustain its achievements after Forward Cities’ engagement ended. “At the end of the day, I would think Forward Cities would want to leave having empowered the community to do these things themselves,” she said, “versus coming in and doing them and leaving.”

The Forward Cities approach actually centers on doing just that, and the fact that local partners were brought in to provide sustainable resources and partners speaks to the value add of these types of engagements, even though to some extent it ends up leading to some ceding of control on the local level to get there. In the end, empowering the community is very much the intention of the project’s leaders. “The purpose of Forward Cities is to work ourselves out of a job,” said Louis. “We get things started and get conversations started, and then the program gets passed on to partner organizations.”

Most New Kensington leaders feel the project has been a major success. The question is just to what extent that success can be sustained. “I think everything that was explained to us in the beginning has occurred,” said Guzzo. “As with every project, there’s a rainbow situation where there’s skepticism and then there’s the buy-in and then there’s the dropoff. These things are great. They have to be consistent. They have to continue.”

All three of the solutions created by the Innovation Council are continuing in some form, owned by groups continuing to work in the community. “In some ways, you have to look at what has come out of that process. What was the result?” said Koch. “There is further development of the programs that were originally started. To me it indicates the solutions are connected to the need. If they weren’t connected to the need, then they would have failed from the get go. It shows they support the community.”

As for Nicole Vigilante, she opened her brick-and-mortar store, first as a pop-up shop and then with more regular hours. Then COVID hit and shut down everything, including her store. But she opened back up in June, and though business isn’t always steady—“there are days that are great and days that are not,” she said—the lessons she learned in the course have continued to help her. The ones that stuck with her most dealt with knowing your customer: targeting the right audience and not being offended when people leave the shop without buying anything.

The grant she received from the program allowed her to buy new products for her shop. And as for the downtown community around her, she says the impact of the Forward Cities initiative has been undeniable in building momentum for local businesses. “It’s almost like a freight train rolling down a hill,” she said. “There’s a lot of smaller businesses.”

But the most useful thing about the project, she said, was the way it brought the community together. She’s still close with people in her Co.Starters cohort. In fact, when we spoke in early November, she and another participant in her course had just given a talk to a group of high school seniors at the local vocation-technical school about entrepreneurship and their businesses. “So we remain connected to the community and to each other, and just super supportive on social media and out and about,” she said. “And I think that is the most impactful thing that has happened to me.”

About the Author: Aaron Wiener is a senior editor at Mother Jones magazine and former housing and development reporter for Washington City Paper. His work has appeared in The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, Slate, and The New Republic.